FREIGHT RAIL OPERATIONS KEY FACTS

- Freight rail runs on a nationwide network of trains, tracks, and signals.

- Yards and dispatch centers manage movement with remote control, sensors, and PTC.

- Railroads maintain safety using drones, detectors, and automated inspection tools.

Freight railroads account for roughly 40% of U.S. long-distance freight volume (measured by ton-miles) — more than any other mode of transportation. North America’s freight rail network includes six Class I railroads, more than 20 regional (Class II), and around 600 short line (Class III) railroads. Class I railroads handle long-haul freight, while regional and short lines connect local industries, often providing first- and last-mile service. Unlike Europe, where passenger rail service dominates operations along publicly-funded tracks, North America’s freight rail system is largely private, with over 70% of Amtrak’s travel occurring on freight-owned rails.

Moving freight safely and efficiently requires seamless coordination of logistics, technology, and engineering. Freight railroads depend on a vast network of locomotives, railcars, tracks, bridges, and yards, with Class I railroads investing billions annually to maintain and modernize this critical infrastructure for the nation’s economy today and tomorrow.

Freight Rail Locomotives

Locomotives are the powerhouses of the rail network, available in various models and configurations. Railroads often rebuild or upgrade older units with modern emissions and safety technologies to extend their lifespan and improve performance. Today’s locomotives are highly fuel-efficient and equipped with hundreds of sensors that monitor everything from engine performance to braking and fuel usage in real time. When locomotives reach the end of their service life, railroads recycle or repurpose many of their components—like steel frames, engines, and electronics. Railroad employees regularly inspect and maintain locomotives to ensure safe and efficient operation.

- Diesel-Electric Locomotives: The standard for most freight trains today. A diesel engine provides the power to operate electric traction motors that drive the wheels. Freight railroads are using biofuels in these models to further reduce emissions.

- Battery-Electric and Hybrid Prototypes: Railroads are testing these for use in line haul service to reduce emissions even further.

- Remote-Controlled Locomotives: Used in yards for switching with the operator nearby controlling the movement.

- Distributed Power Units (DPUs): Locomotives placed mid-train or at the end, controlled remotely from the lead unit.

Freight Railcars

Railroads purpose-build railcars for different commodities, but they own only a minority—especially tank cars. A mix of entities owns and maintains most railcars, including railroads (particularly for specialized fleets or system-wide service), shippers (companies that move large volumes of goods and often own or lease their own cars), and leasing companies (which own tens of thousands of cars and lease them to railroads or customers). Regardless of ownership, all railcars must meet strict federal safety and inspection standards. The most common types of freight railcars include:

Boxcars: Enclosed cars used for general freight like appliances, paper, and packaged goods.

Flat cars: Open-deck cars for oversized or irregular loads like steel beams, lumber, or machinery.

Hopper Cars: Covered hoppers carry dry goods like grain or fertilizer while open hoppers carry coal, aggregates, or ore.

Tank Cars: These cars safely carry liquids and gases, including chemicals and fuels. Safety regulators heavily regulate tank cars. Freight railroads have long advocated for even tougher standards.

Gondolas: Open-top cars used for scrap metal, gravel, or coils.

Well Cars: Designed to carry intermodal containers. The lower center of gravity helps with speed and safety.

Autoracks: Also called a multilevel carrier, this railcar is an enclosed or partially enclosed railcar used to move new automobiles, SUVs, trucks, and vans from manufacturing plants to distribution centers. Autoracks protect vehicles from weather, theft, and damage in transit.

Centerbeam Cars: Specialized flatcars used for lumber, drywall, and other building materials.

Freight Rail Wheelsets & Couplers

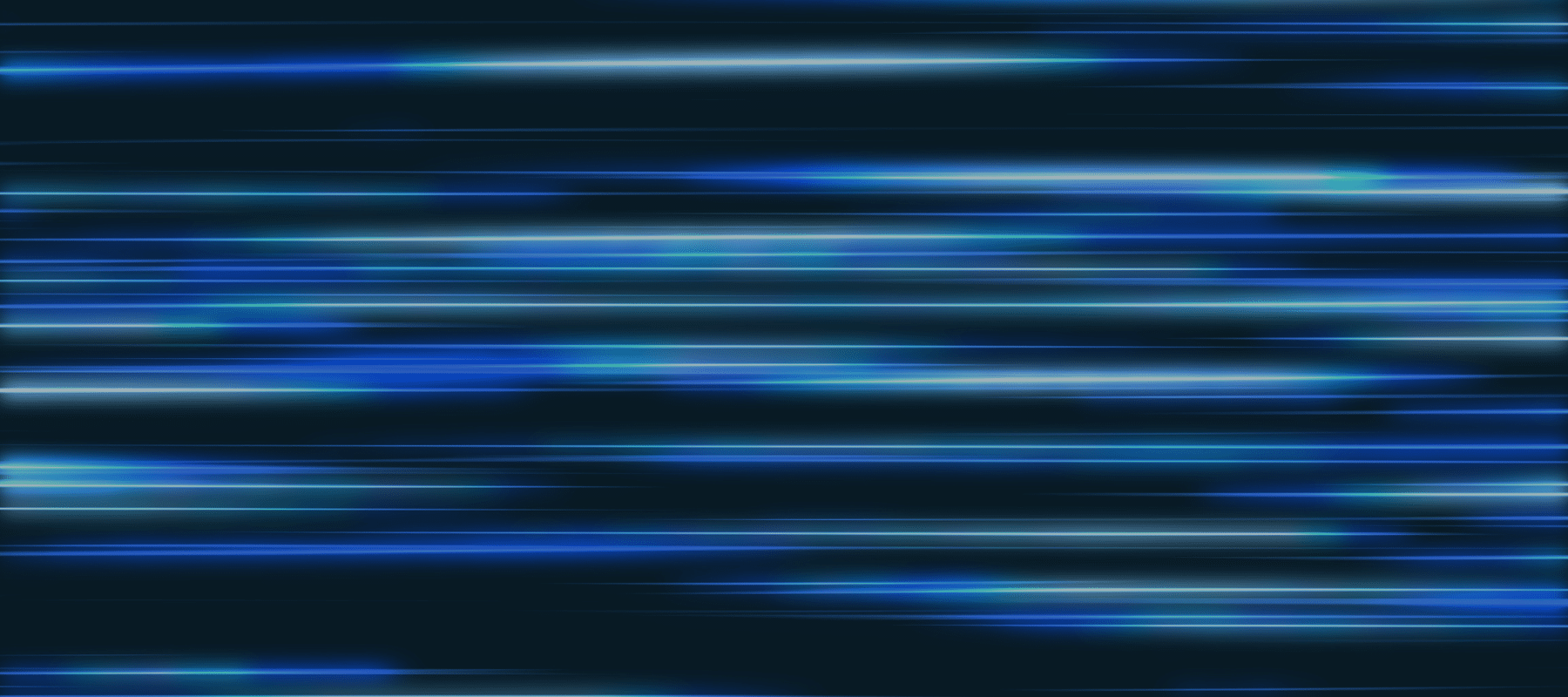

A freight train truck (also known as a bogie) is the framework that supports the wheels and axles underneath each freight car. It’s a critical component of the railcar’s suspension and running system. Inspectors inspect wheelsets regularly—both manually and by trackside detectors—to catch defects before they cause issues. Together, wheelsets and couplers ensure that heavy trains can run safely, securely, and reliably across thousands of miles.

A wheelset includes two solid steel wheels mounted on a single axle. These components support the weight of the railcar, guide it along the rails, and absorb massive forces in motion. Key parts include the:

- Wheels: Designed to withstand extreme loads and friction).

- Axles: Connect the wheels and rotate with them).

- Bearings: Help the axle spin efficiently and safely).

Couplers are the heavy-duty links that connect railcars together. In North America, most freight railcars use knuckle couplers, which automatically lock when two cars are pushed together. Adjacent to couplers are air hoses for the braking system. End-of-train (EOT) devices, which is modern technology that replaces the old caboose, attach to the coupler and monitor brake pressure and train performance.

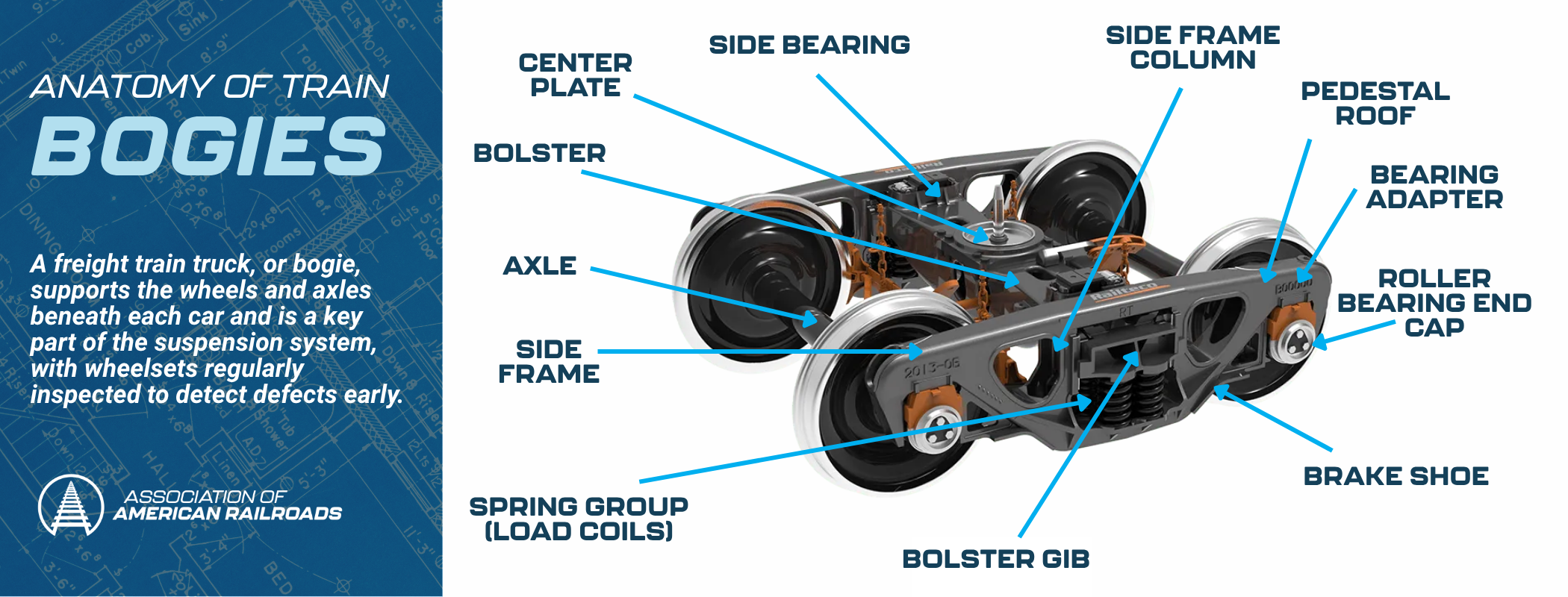

Freight Rail Track Infrastructure

The rail network includes several types of track, each serving a specific role in keeping freight moving safely. Railroads invest heavily in maintaining this infrastructure, using advanced tools like track geometry cars and ultrasonic detectors to inspect for wear or hidden defects.

When needed, railroads replace track components as part of regular capital programs, swapping or recycling rails, replacing ties in large batches (with wood ties often repurposed), and cleaning or refreshing ballast to ensure proper support and drainage. This proactive approach keeps the network safe, durable, and ready for heavy freight demand. Key components of rail track include:

- Rails: Made of hardened steel, rails guide train wheels and bear the full weight of passing trains. Rails are fastened to ties and welded together in long segments to reduce joints and ensure a smoother ride.

- Ties (or Sleepers): These crosswise beams—made of wood, concrete, composite material, or sometimes steel—hold the rails in place and transfer the load from the rails to the ground. Wood ties are still common but are gradually being replaced by longer-lasting concrete ones on many high-traffic routes.

- Ballast: Crushed rock packed beneath and around the ties. Ballast provides stability, drains water, and helps distribute the enormous pressure exerted by passing trains.

- Subgrade: The compacted soil or foundation layer beneath the ballast, which must remain firm and properly drained to support the track structure above.

Types of rail track include:

- Double/Triple Track: Parallel tracks on the same corridor, used to increase capacity and efficiency.

- Industrial Tracks: Spur tracks branch off the mainline serving individual facilities like factories or grain elevators. Industry tracks are privately owned and connect to customer sites for direct rail access.

- Mainline Track: The backbone of the system—built for long-distance travel, high speeds, and heavy loads. There are nearly 140,000 miles of mainline track across North America.

- Yard Tracks: Low-speed tracks within yards for sorting, switching, and storage.

Freight Rail Yards & Shops

Freight railroads invest heavily in rail yards to improve efficiency, capacity, safety, and environmental performance. These facilities are essential for assembling, disassembling, and sorting trains, and Class I railroads dedicate a significant portion of their annual capital spending to yard modernization.

Investments focus on automation and technology to streamline switching and car tracking, expanded intermodal terminals to handle growing container traffic, and cleaner equipment to reduce emissions. Railroads are also upgrading yard layouts, support tracks, and infrastructure to reduce congestion and improve turnaround times. Safety enhancements, such as improved lighting, signaling, and secure access systems further ensure that yards operate smoothly as key links in the freight rail network.

- Hump Yards: These large, automated yards use gravity to sort railcars. Trains are pushed over a small hill (the “hump”), and cars roll down into specific tracks based on destination. They’re great for high-volume sorting.

- Flat Yards: Crews manually sort and assemble trains using locomotives to move railcars. These are more flexible than hump yards and are used in smaller or more specialized locations.

- Intermodal Terminals: Designed to transfer containers between trains and trucks. These yards feature cranes, straddle carriers, and modern tracking systems to support fast, efficient intermodal movement.

Freight rail shops are specialized facilities where locomotives and railcars are inspected, maintained, repaired, and overhauled. From routine servicing to complex rebuilds, rail shop workers are skilled professionals that use various technologies to keep the freight rail network running smoothly. Facilities can range from small service points to large-scale maintenance hubs supporting entire rail fleets.

Freight Rail Signals & Switches

Freight railroads rely on their own network of signals and switches to direct train movements across their vast networks. These systems help control traffic, prevent collisions, and ensure trains are routed correctly. On busier routes, railroads use computerized dispatching systems to control signals and switches, optimizing traffic flow and preventing conflicts in high-traffic areas as well as Positive Train Control (PTC). Together with human expertise, these technologies help make a safe network even safer.

Railroad signals communicate movement instructions to train crews, much like traffic lights for cars. They indicate when a train should stop, proceed, or slow down based on track conditions. There are two primary types:

- Fixed: Stationary signals along the tracks that use lights to convey instructions

- Cab: Displays movement authority inside the locomotive, often as part of PTC systems.

Common signal meanings include: Green (Clear): Train may proceed at maximum authorized speed; Yellow (Approach): Train must slow down and prepare to stop at the next signal; and Red (Stop): Train must stop. Some signals also include additional indicators for speed restrictions, track changes, or special conditions.

Railroad switches, also known as turnouts, allow trains to move from one track to another. These are essential for routing trains, enabling passing, and organizing rail yards. Types of switches include:

- Manual Switches: Operated by railroad workers on the ground.

- Power Switches: Controlled remotely from a dispatching center.

- Crossover Switches: A pair of switches enabling a train to move from one parallel track to another.

Bridges & Tunnels

Bridges and tunnels are essential to freight rail since they provide direct routes across difficult terrain. Heavily regulated by federal safety standards, freight railroads monitor bridges and tunnels through regular inspections and tools like drones, sensors, and laser mapping to catch issues early.

- Bridges: There are more than 60,000 rail bridges in the U.S., most of them privately owned and maintained by freight railroads. Railroads handle regular inspections, maintenance, and upgrades to support today’s heavier, faster trains. While surface rust is common, it’s usually cosmetic and not a safety issue. Bridges vary widely in type and age—from modern concrete spans to 100-year-old steel or wooden structures still in service thanks to continuous investment.

- Tunnels: Tunnels allow trains to pass through natural or man-made barriers like mountains, hillsides, or dense urban areas. Like bridges, railroads privately own and maintain must tunnels. These structures often date back more than a century and are frequently updated to meet modern safety and clearance standards. Key maintenance responsibilities include drainage systems to prevent water buildup; ventilation systems for longer or more heavily used tunnels; and structural reinforcement and regular safety inspections. Railroads have expanded or modified many tunnels to allow double-stack intermodal trains or to meet higher speed and clearance requirements.

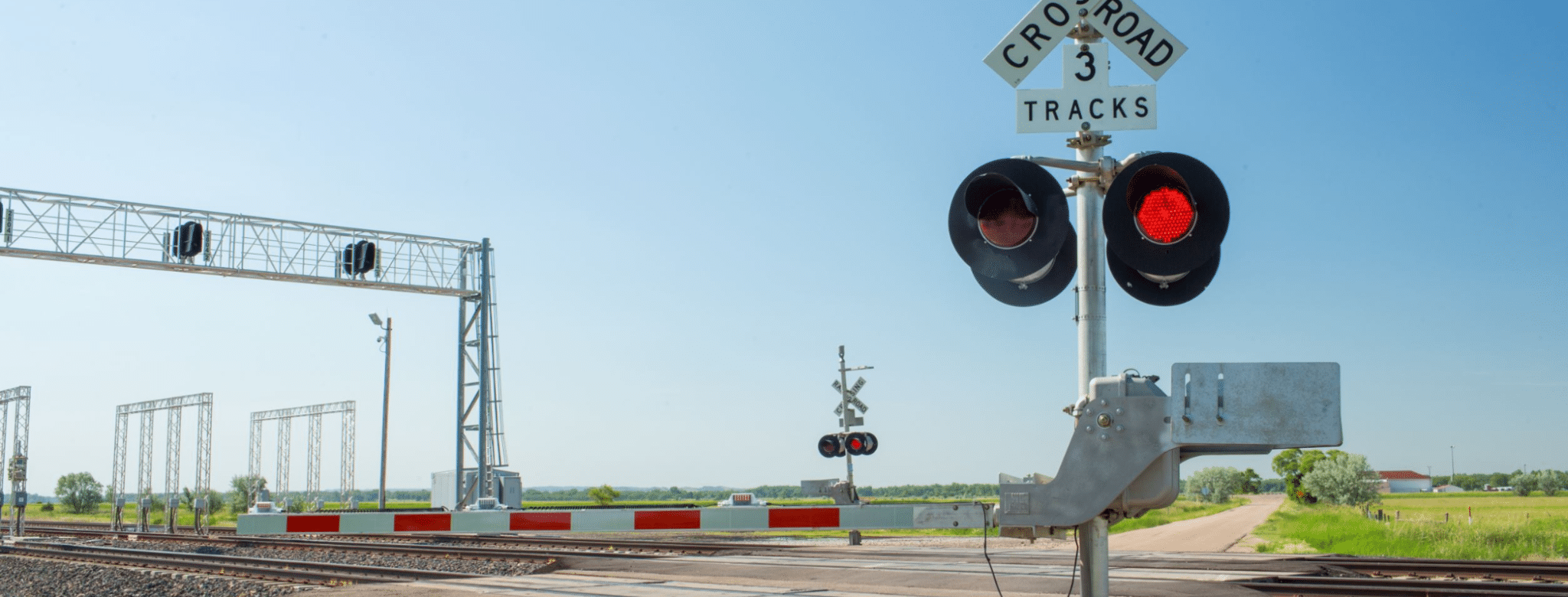

Grade Crossings

There are more than 200,000 grade crossings across the United States, where rail lines intersect with roads at the same level. Maintaining these crossings is a shared responsibility: railroads oversee the track, signals, and warning systems within the crossing itself, while state or local governments typically maintain the road surface and signage.

Despite ongoing safety gains, grade crossing and trespassing accidents remain the leading causes of rail-related injuries and fatalities, accounting for over 95% of all incidents. While the total number of public crossings has declined by 12% since 2005 and the percentage of crossings equipped with gates increased from 26% to 45%, the grade crossing accident rate improved just 4% over the period, underscoring the critical need for further action.

Investments in infrastructure, public safety campaigns and collaboration with government and community partners are all important elements in the effort to reduce grade crossing and trespasser accidents. Programs like the Grade Crossing Elimination Program and Section 130 provide essential funding that enables communities to build grade separations, close crossings and upgrade warnings systems. Continued investments in these programs are vital to reducing risk across the nation.