For nearly 200 of America’s 250 years, railroads have helped shape the country—building connections, driving growth, and supporting communities in ways few other industries can match. Freight rail has grown with the nation—from early wooden bridges and steam engines to today’s modern trains and digital technology.

This “Then & Now” look explores that transformation: how railroads grew from frontier‑spanning experiments into one of the most reliable, efficient, and innovative freight systems in the world. It’s a story of steady progress and American ingenuity—of an industry that helped build the country and continues to keep it moving every day.

1. Cabooses: From Rolling Offices to Digital End-of-Train Eyes

THEN: For generations, cabooses marked the end of freight trains and served as mobile workspaces for crew members. From the rear of the train, crews watched for smoke, shifting loads, hot bearings, and mechanical issues. Cabooses also provided protection during switching and emergency stops.

NOW: Today, end-of-train devices, also known as Flashing Rear End Devices (FREDs), handle caboose responsibilities. These electronic systems transmit real-time data on brake pressure, movement, and train integrity directly to the locomotive, improving situational awareness while allowing crews to remain safely in the cab.

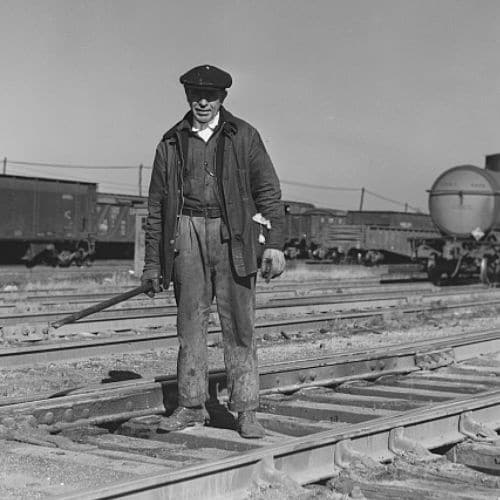

“Amarillo, Texas. R.W. Simmons, an Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe engineer, boarding a caboose.” Jack Delano. March 1943 for the Office of War Information.

Modern day end-of-train device. Image courtesy of Norfolk Southern, 2019.

2. Steam Trains: From Fire & Water to Power & Precision

THEN: Steam locomotives powered early freight railroads — engineering breakthroughs of their time, but demanding to operate. Steam engines required constant supplies of coal and water, frequent stops along the route, and intensive hands-on maintenance by large crews. Range, speed, and reliability were all constrained by these limits.

NOW: Today, freight rail relies primarily on diesel-electric locomotives, which generate electricity onboard to power traction motors. This technology allows trains to travel much longer distances, haul heavier loads, and operate with greater reliability and efficiency. Advances such as distributed power (adding a locomotive into the middle of the train), onboard fuel management systems, and emerging alternative fuel technologies continue to push performance even further while driving down freight rail’s already small carbon footprint.

Tennessee Valley Authority. Railroad crews at Watts Bar Dam. Clearing the sand line is one of the chores that fall to the “tallow pot,” or fireman, of a railway locomotive. In addition to jobs like this, the “tallow pot” serves up an average of eight to ten tons of coal each eight hour day to the big “hog,” or locomotive. This man fires a train carrying materials for the building of TVA’s Watts Bar Dam. 1942, Library of Congress.

Modern day diesel locomotive.

3. Paper Timetables: From Printed Schedules to Real-time Networks

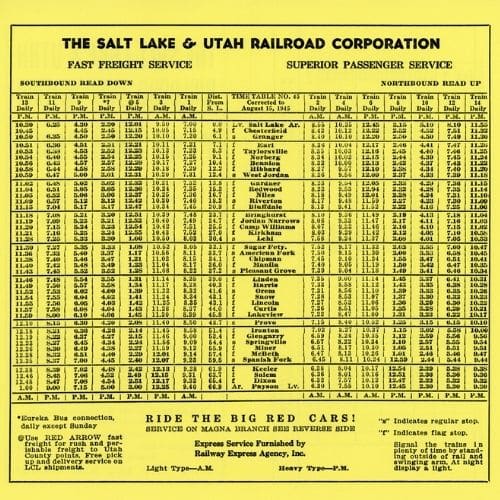

THEN: In the 19th century, freight rail operations depended on printed timetables, pocket watches, and strict adherence to schedules. Trains shared single-track lines, and crews relied on timed separation — often waiting at sidings — to prevent conflicts. Accuracy mattered, and even small errors could have serious consequences.

NOW: Freight railroads manage their networks through centralized traffic control and digital dispatching systems that monitor train locations in real time. Dispatchers can adjust movements dynamically, coordinate traffic across long distances, and respond quickly to changing conditions — improving both safety and reliability across a far more complex system.

Inside of the Salt Lake and Utah Railroad’s timetable number 45. Showing the timetable for the mainline. Published in 1945, one year before the railroad was closed.

A modern day dispatcher.

4. Manual Labor: From Muscle Power to Automated Control

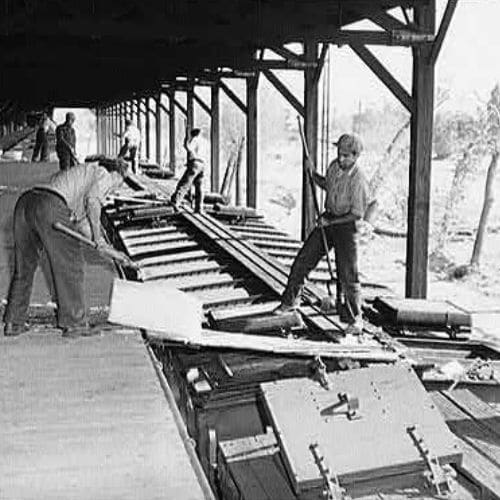

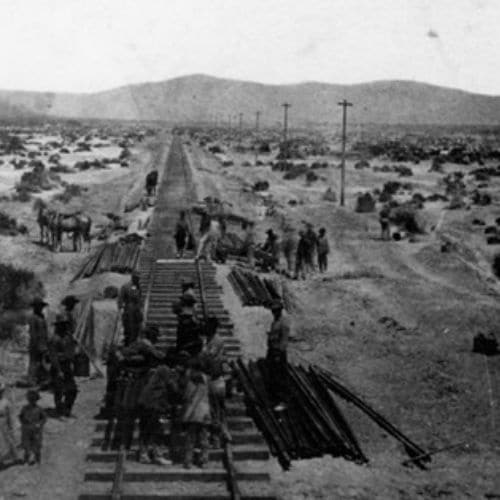

Then: In the early days of freight rail, nearly every task depended on human muscle and experience. Goods were loaded and unloaded piece by piece—barrels, crates, sacks, and boxes handled manually at every transfer point—adding time, cost, and risk of damage. Brakemen climbed moving railcars to apply hand brakes in all weather, making one of the most dangerous jobs in railroading even riskier. At the same time, railroad networks themselves were built almost entirely by hand. From the 1820s through the late 1800s, crews graded land with picks and shovels, laid ties one by one, and spiked rails into place, creating tens of thousands of miles of track that formed the backbone of the nation’s freight system.

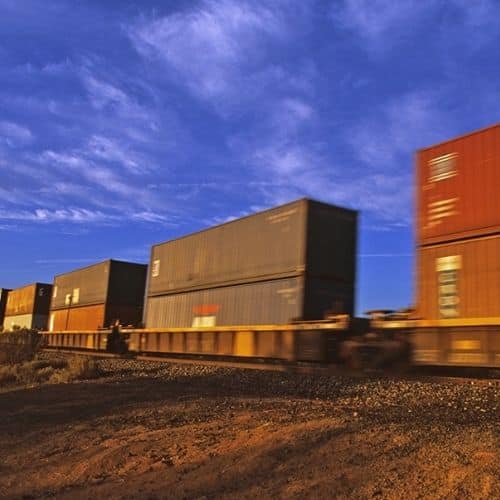

Now: Modern freight rail relies on automation, standardization, and precision engineering. Intermodal containers move seamlessly between ships, trucks, and trains without being opened or repacked, reducing handling, speeding delivery, and improving efficiency while lowering fuel use and emissions. Integrated air brake systems allow engineers to control braking safely from the cab, applying consistent force across entire trains. Rail construction and maintenance now use specialized machinery, sensors, and data analytics to place track with exacting accuracy and monitor infrastructure in real time. Together, these advances allow railroads to move far more goods, far more safely, on a network built to support the demands of today’s economy.

Rail workers manually move one piece of rail. March 1943. Photo by Jack Delano, Office of War Information.

A modern-day machine helps track maintenance workers do their jobs more safely and efficiently. Photo courtesy of BNSF.

5. Telegraph: From Taps on a Wire to Instant Communication

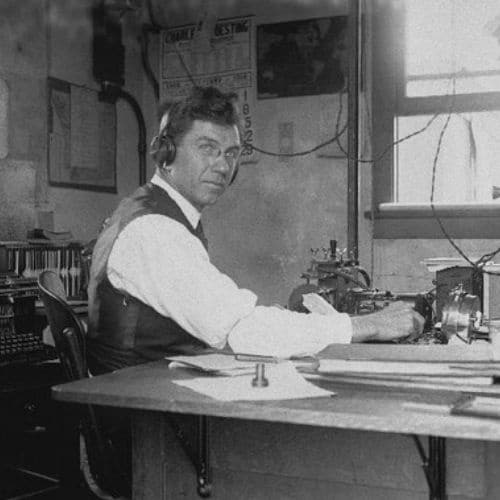

THEN: In the 1800s, telegraph wires ran alongside the rails, forming the backbone of railroad communication. Dispatchers used Morse code to relay train orders across long distances, helping coordinate movements on single-track lines and improving safety in an era before radios or real-time tracking.

NOW: Today, freight rail communication is built on GPS, satellites, and fiber-optic networks. These systems allow railroads to track train location in real time, monitor performance and equipment health, and coordinate movements across a vast national network — supporting safer, more efficient operations at a scale that early railroads could never have imagined.

Telegraph Operator, 1916. Courtesy of San Diego Historical Society.

Modern day dispatchers are surrounded by technology.

6. Light Loads: From Limited Capacity to Heavy Haul Efficiency

THEN: When railroading began in the 1800s, a typical freight train carried a few hundred tons at most. Early railroads were limited by lighter rails and bridges, smaller locomotives, manual braking systems, and shorter train lengths. Although trains were still the heavy haulers of their time, they could only move so much at once.

NOW: Advances in infrastructure, engineering, and operations allow a single freight train to move more than 10,000 tons of goods across the country in one trip. Stronger track, distributed power locomotives, and modern braking and control systems have dramatically increased both capacity and efficiency.

Image of a stream locomotive.

Example of a double-stacked intermodal train.

7. Bridges: From Timber Spans to Engineered Giants

THEN: Early freight railroads relied heavily on wooden bridges and trestles to cross rivers, valleys, and uneven terrain. These structures were effective for their time, but they were vulnerable to weather, rot, fire, and increasing train weights, often lasting only years or a few decades before requiring significant repair or replacement.

NOW: Freight railroads build the majority of their infrastructure with steel and concrete, engineered to support heavier loads and withstand constant use for 50 to 100 years or more.

Erie Railroad’s Wooden bridge over Genesee River north of Portageville, NY. 1875. Library of Congress.

A bridge under construction in New York. Photo courtesy of Norfolk Southern.

8. Raw Goods: From Resource Extraction to Integrated Supply Chains

THEN: In the 1800s, freight railroads primarily moved raw materials — coal from mines, timber from forests, and agricultural goods from farms — supplying the basic inputs that fueled America’s early industrial growth.

NOW: Today, freight rail carries a far broader mix of goods, from automobiles and construction materials to consumer products, food, energy products, and intermodal containers. Rail now supports nearly every sector of the economy, connecting producers, manufacturers, retailers, and consumers across the country. As the economy evolved, so did freight rail — adapting to move what America needs, when and where it’s needed.

Strasburg Rail Road engine 929 in Strasburg, PA in 1894.

Bi-level autorack. Photo courtesy of Union Pacific.

9. Moving People: From Passenger Rail to Freight-first Networks

THEN: In the early days of railroading, freight railroads also operated extensive passenger train service, using the same networks to move both goods and people. Passenger trains shared tracks, stations, and crews with freight, making rail the primary mode of long-distance travel throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

NOW: Modern freight railroads focus primarily on moving goods, while passenger rail operates as a distinct service. Most intercity passenger trains — including Amtrak — run over freight railroad-owned track, reflecting the continued role freight railroads play in supporting passenger mobility. This separation allows freight networks to optimize heavy-haul efficiency while enabling passenger rail to serve key corridors and communities.

A woman reads in bed in pullman car berth. 1905. Library of Congress.

Modern Amtrak sleeper car.

10. Fuel Efficiency: From Guesswork to Data-supported

THEN: In the very first years of railroading, fuel efficiency wasn’t measured or tracked. Steam locomotives burned coal fuel oil and consumed water continuously, and moving freight was the focus, not maximizing how efficiently it moved.

NOW: Today, fuel efficiency is a core performance metric. Modern freight railroads use advanced locomotives, operating practices, and data analytics to move more freight using less fuel, making rail the most fuel-efficient way to move goods over land. One train can move one ton nearly 500 miles on one gallon of fuel and trains are three to four times more fuel efficient than trucks, on average. That efficiency translates directly into lower emissions and a smaller environmental footprint as freight volumes continue to grow.

A New York, Ontario & Western (NYO&W) steam locomotive pulls a freight train on a snowy day in the mid-1930s.

Union Pacific locomotive engineers use EMS to optimize train handling while driving down greenhouse gas emissions.

11. Milk & Ice Trains: From Racing the Clock to Built-in Cold Chains

THEN: From the mid-1800s through the 1940s, railroads were essential to keeping food fresh in growing cities. Ice trains carried harvested natural ice from rural regions to urban markets, supporting food preservation, brewing, medical care, and industrial cooling. At the same time, tightly scheduled milk trains ran overnight from dairy farms to cities, using iced railcars and priority handling to prevent spoilage. Railroads coordinated closely with dairy cooperatives, and even minor delays could ruin entire shipments. Together, ice and milk trains formed the backbone of pre-refrigeration supply chains, moving freshness itself before mechanical cooling and highways existed.

Now: Mechanical refrigeration, refrigerated trucking, highways, and regional processing plants eliminated the need to ship ice or operate dedicated milk trains. Cooling is now built directly into railcars, warehouses, and equipment, transforming how perishables move. Rail’s role shifted from transporting ice and raw milk under extreme time pressure to efficiently moving finished dairy and frozen products in modern refrigerated railcars, known as reefers. In fact, freight railroads invest heavily in this technology to move the goods American families depend on. While the methods have changed, rail remains a vital part of today’s temperature-controlled supply chains.

Men load ice blocks into older versions of the reefer car. Library of Congress.

In 2023, CPKC added 1,000 new, 53-foot, refrigerated intermodal containers to its transnational, single-line service network.

12. New Technology: From Novelty to Necessary

THEN: When railroads emerged in the 1830s, they were revolutionary technology. Trains moved people and goods faster and farther than ever before, shrinking distances, opening new markets, and reshaping how the country grew. Railroads were symbols of innovation — bold, visible, and transformative.

NOW: Freight rail is no longer novel — it’s trusted infrastructure. It operates largely out of sight, moving the goods that keep supply chains running and the economy functioning every day. What once disrupted the status quo now provides reliability, scale, and resilience — quietly supporting commerce across the nation. That evolution reflects success: when a technology works well enough, it becomes something the country depends on.

Great Northern 4-4-0 locomotive William Crooks, 1861. Lake Superior Railroad Museum, Duluth, MN.

Seal of the City of Houston.

Today, freight railroads are part of the American landscape.

13. News by Train: From Railcar Headlines to Instant Updates

THEN: In the 1800s, railroads didn’t just move freight — they moved information. Newspapers, letters, and packages traveled by train, meaning news spread at the speed of the rails. For much of the country, rail was the fastest and most reliable way ideas, updates, and mail reached new communities. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, rail became central to the nation’s mail system, with postal clerks sorting letters onboard moving trains to speed delivery and to help unify the country.

NOW: Today, information and mail move primarily by digital networks, trucks, and air. Freight rail’s role has evolved, but its importance hasn’t. While data travels instantly, freight rail continues to move the goods that keep the economy running — reliably, day and night.

Sorting out the US Mail in a rail car. 1910.

Modern freight railroads move just about everything.

14. Military: From Mobilizing Armies to Moving Global Defense

THEN: In the 19th and early 20th centuries, freight railroads played a critical role in moving U.S. military troops and equipment, especially during major conflicts. Trains enabled the rapid mobilization of large forces across long distances — something no other mode of transportation could match at the time.

NOW: Military transportation relies on a mix of air, truck, and sealift, while freight rail continues to support national readiness by moving heavy equipment, vehicles, and supplies efficiently across the country. Freight railroads are also still a strong partner with the military; one in six freight rail employees are veterans.

U.S. soldiers wave farewell, American troop train leaving a Midwestern U.S. military camp, WWII.

U.S. Army Photo by Scott T. Sturkol, Public Affairs Office, Fort McCoy, Wis.

15. Domestic Trade: From Stock Cars to Specialized Transport

THEN: In the early days of railroading, freight rail primarily served local and regional markets, moving goods from farms, mines, and factories to nearby towns, ports, and industrial centers. These early rail lines were often short and disconnected, designed to meet immediate economic needs rather than support long-distance trade. Still, they helped standardize commerce, reduce transportation costs, and knit together growing regional economies — laying the foundation for a national network.

NOW: The freight rail network operates at an entirely different scale. Freight railroads carry about 40% of all long-distance freight moved in the United States, connecting producers, manufacturers, ports, and consumers across thousands of miles. What began as a regional solution has evolved into a core pillar of the national supply chain, supporting industries and communities coast to coast and globally.

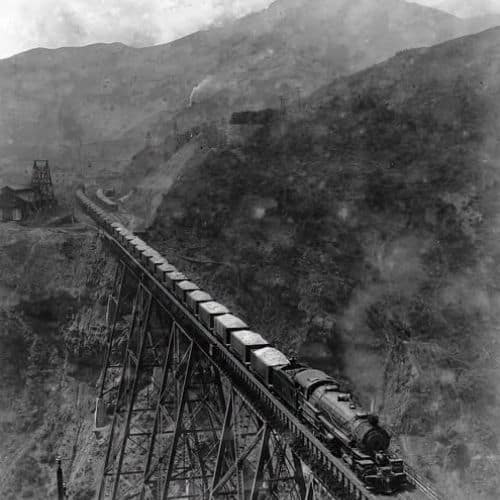

A train hauls copper ore over a high trestle at Bingham, Utah ca. 1914. Photo courtesy Western Mining History.

Aerial view of the BNSF Northtown Yard, a large freight rail yard located in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

16. Live Animals: From Stock Cars to Specialized Transport

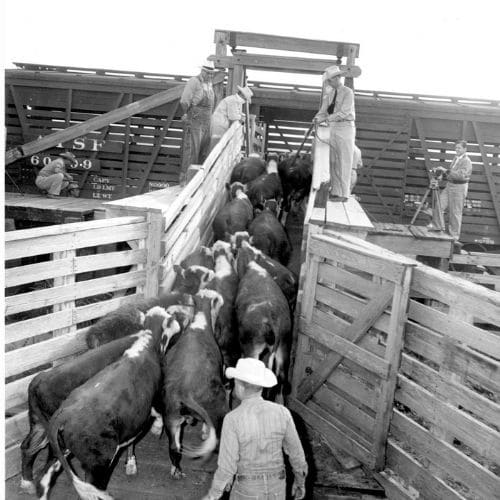

THEN: Between the 1870s and 1950s, railroads enabled the rise of centralized stockyards and national meatpacking by making it possible to move live animals hundreds or thousands of miles. Specialized stock cars included ventilation and watering systems, and federal regulations governed rest stops and care during transit. Rail was essential to scaling livestock markets and supporting urban populations far from agricultural regions.

NOW: Changes in food production, animal welfare expectations, and logistics reduced the need for long-haul live animal transport. Processing facilities moved closer to farms, and trucking offered greater flexibility for shorter trips. Rail continues to move animal feed and refrigerated meat products rather than live animals.

Loading Cattle into Railroad Cars at the Stockyards, photograph, Date Unknown; University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, crediting Cattle Raisers Museum.

A freight train moves grain.

17. Home Moving: From Boxcars to Door-to-Door Logistics

THEN: From the 1800s through the 1950s, freight railroads enabled long-distance household moves by allowing families to ship furniture, appliances, and personal belongings in freight cars. For many Americans, rail was the only practical and affordable way to relocate across states or regions. This service supported westward expansion, the movement of workers to growing industrial centers, and the rise of urbanization, making large-scale migration possible in a way no other mode of transportation could match at the time.

NOW: As transportation options expanded, rail’s role evolved. The growth of highways, trucking, and specialized moving companies shifted household moves toward door-to-door service, offering greater flexibility and convenience. Freight rail increasingly focused on what it does best — moving commercial goods at scale over long distances — while personal relocations transitioned to modes better suited for individualized delivery.

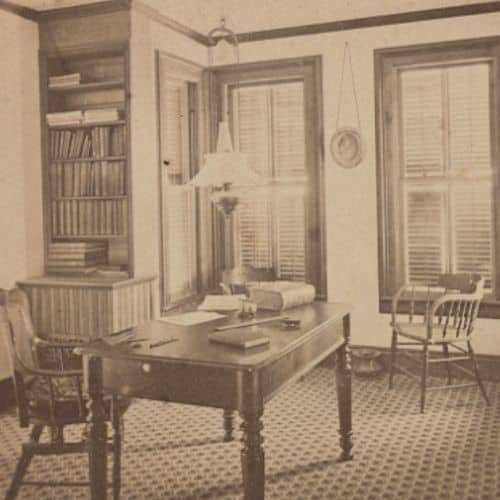

Interior of a home from around 1870. Library of Congress.

An intermodal train moves over a rail bridge. Intermodal is used to move almost anything that can fit into a container.

18. Investments: From the Ground Up to Billions Each Year

THEN: In the 19th and early 20th centuries, freight rail investment focused on building reach. Capital went toward laying new track, expanding westward, constructing bridges and terminals, and connecting farms, mines, and factories to markets. Much of this investment was driven by private capital and reinvested earnings, with railroads rapidly building physical infrastructure to support a growing nation. The priority was expansion — getting rails where none existed before.

NOW: Freight rail investment is focused on modernization, resilience, and capacity. Railroads privately invest billions of dollars each year to maintain and upgrade existing infrastructure, deploy advanced technologies, improve safety systems, expand intermodal terminals, and strengthen bridges and track to handle heavier loads and higher volumes. Rather than expanding the footprint, today’s investments are about making the network safer, more efficient, and more reliable — ensuring it can support modern supply chains and economic growth for decades to come.

Central Pacific workers lay rail at the end of track, Humboldt Plains, Nevada. 1868. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

One example of the many investments Class I railroads make: CSX reopened the expanded Howard Street Tunnel in fall 2025, removing a major East Coast bottleneck and paving the way for double-stack container trains through Baltimore.

19. Jobs: From Railroad Towns to High-skill Careers

Then: In the late 1800s and early 1900s, freight railroads were among the largest employers in the United States and a powerful engine of middle-class growth. Railroad jobs—ranging from track laborers and car inspectors to clerks, engineers, and conductors—often provided steady wages, housing, healthcare through railroad hospitals, and some of the nation’s earliest pension systems. Railroads helped standardize wages, professional training, and labor protections, allowing millions of workers, including many immigrants and rural Americans, to achieve economic stability and upward mobility.

Now: Freight rail jobs remain among the best-paying in the nation, with wages averaging about 40% higher than the national average. Railroad employees also tend to build long careers—the median tenure is nearly 14 years—and more than 80% of Class I railroad workers are unionized. Today’s railroad careers blend skilled trades, advanced technology, and safety-critical operations, offering strong pay, comprehensive benefits, and secure retirement plans. By providing stable, long-term careers that often do not require a college degree, freight railroads continue to support middle-class livelihoods while playing a vital role in moving the nation’s goods and sustaining the modern economy.

An employee of the yard gang cleans out switches at an Illinois Central Railroad yard. 1942. Library of Congress.

A modern day freight rail employee.

20. Moving Big Stuff: From Industrial Giants to Space-age Cargo

Then: From the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, freight railroads were the only way to move the largest and heaviest objects ever built. Entire steam locomotives were shipped fully assembled from factories to railroads across the country. Rail also carried massive industrial boilers, steel mill equipment, bridge girders, stone blocks for courthouses and monuments, as well as enormous naval guns and military hardware during wartime. These oversized loads powered industrialization, electrification, and national defense at a scale no other transportation system could match.

Now: Today, freight railroads continue that role by moving some of the most advanced and oversized cargo in the modern world. Specialized railcars transport rocket boosters and spacecraft components, massive power transformers, nuclear reactor parts, and wind turbine blades stretching hundreds of feet long. Rail also carries prefabricated bridges and large modular structures that support modern infrastructure and energy systems. While the cargo has evolved from steam and steel to space and renewables, rail remains essential for moving the biggest things humans can build—too large, heavy, or fragile for highways.

Finished engine at 20th Street round-house, ready for shipment, Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia, Pa., U.S.A. 1900-1910. Library of Congress.

BNSF moves new Boeing 737 rocket engines. Photo: RailPictures.net Image Copyright Allen Robertson.