FREIGHT RAIL ENGINEER & CONDUCTOR TRAINING KEY FACTS

- Conductors and engineers undergo months of intensive training.

- Engineers are promoted from conductor roles.

- Ongoing testing ensures safety and performance.

Freight railroads provide the safest way to move goods over land. Rail employees make this possible by committing to safety from the moment they apply. Railroads prioritize protecting communities and the employees who operate their trains.

Training is extensive, especially for conductors and engineers. Candidates train for months to become conductors, and years of experience are usually required to advance to engineer. Training combines classroom instruction, hands-on experience, and ongoing exams. Railroads use technology, proven protocols, and senior mentors to ensure conductors and engineers are fully prepared before operating a locomotive alone.

Becoming a Conductor

Becoming a conductor is the first step toward becoming an engineer. Training never ends—conductors and engineers must demonstrate safe operations throughout their careers.

- Classroom Learning: During the first two weeks of training, trainees focus on core safety principles at railroad facilities. They learn how to move equipment safely, understand operating rules and signals, and master essential reporting systems. This includes documenting work, processing payroll, and logging hours of service to meet regulatory requirements.

- Field Training: For the last two weeks, trainees move to an outdoor railroad training center to learn the fundamentals of train movements. This includes how to move railroad cars around a dedicated training yard safely, do shoving movements, secure brakes, inspect equipment, conduct brake tests, and use hand signals with specialized lanterns. Trainees repeat these actions over and over until they become second nature.

- Proficiency Exams: Throughout initial training, railroads will test trainees repeatedly with quizzes and cumulative tests. They must maintain 85% or higher to advance to in-service training.

- On-the-job Training: After initial training, trainees work with a certified conductor for two to four months or more, depending on location complexity. Rural areas may be simpler than busy urban hubs or ports. Trainees are closely supervised and follow a site-specific training plan set by the local manager. Regular check-ins help track progress and address issues. If the location uses remote control locomotive systems, trainees receive 80+ hours of specialized classroom and field training. This helps them to learn how to operate locomotives via an Operator Control Unit outside the cab.

- Graduation: The local manager must assess a trainee’s proficiency in several core competencies before they can graduate. The trainee must also pass a physical characteristics exam. This exam tests their knowledge of the rail network within their territories, including the location of switches, how many there are, their numerical designation, or the layout of a customer’s facility.

Advancing to Engineer

The engineer operates the locomotive. They control the speed and direction of the train, inspect the locomotive before use, and monitor the trip’s progress by observing wayside signals and signs. They also observe instruments in the cab detailing train speed, the status of braking systems, and other information.

- Starting with Seniority: Railroads select engineer trainees from the conductor ranks based on seniority and years of experience. Rising to an engineer requires several years working as a conductor and another five to six months of on-the-job training before gaining certification.

- Classroom Learning: Trainees first undergo several weeks of classroom instruction, computer-based instruction and assigned self-study. Training topics include setting up locomotives, handling air brakes, inspecting equipment and troubleshooting.

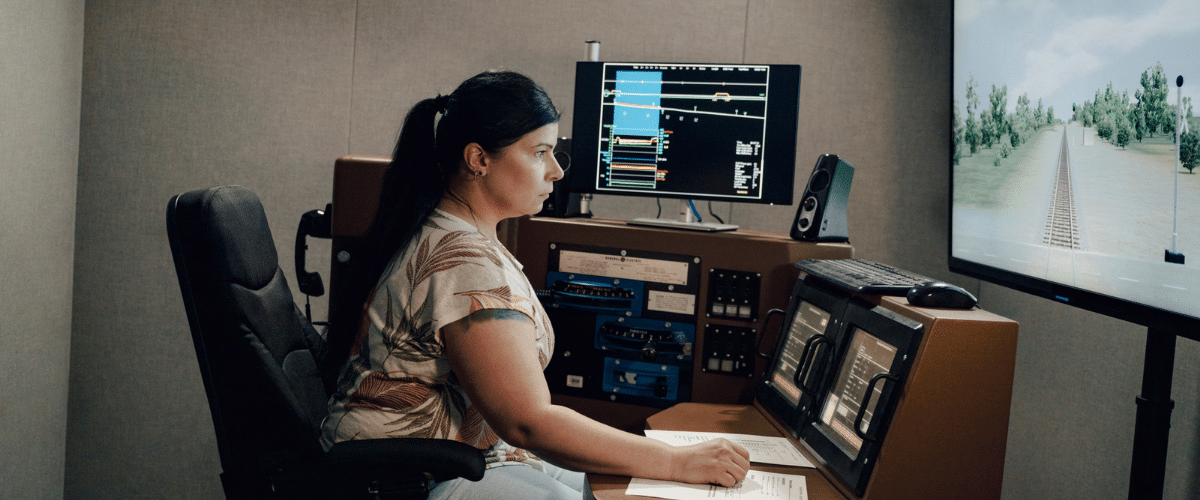

- Virtual Learning: Trainees spend up to three hours daily on simulators, applying class and self-study materials. Simulated runs often reflect real territories they’ll work in. This hands-on practice builds muscle memory and helps trainees quickly learn to handle common and rare scenarios, like heavy trains in mountainous areas.

- Ongoing Exams: Like conductor training, an engineer trainee must pass a series of exams. These include the rules for operating a train, mechanical knowledge — such as identifying the different parts of a locomotive and how they work together — and railroad signals.

- Field Training: If the trainee passes their tests, they return to their home location to begin on-the-job training that lasts five to six months. They will work alongside a certified engineer to operate across their territory. They can’t work alone during this time. Federal certification programs require trainees to prove they can perform the most demanding class or type of service they are authorized to handle.

- Regular Evaluations: The local manager evaluates the trainees regularly. They must demonstrate proficiency in approximately 20 areas, including properly complying with speed restrictions and wayside signals, inspecting and setting up locomotives, or conducting brake tests. In addition, the manager will assess how the trainee performs by examining electronic recordings of their train trips that capture the trains’ speed and movements.

- Graduation: A designated supervisor will take a final ride with the trainee. Before officially promoting a trainee from conductor to engineer, the supervisor evaluates the trainee’s performance. They take into account their training history and discussions the supervisor has had with coach engineers.

Training never ends.

Railroads provide ongoing training and assessments for conductors and engineers. Conductors periodically recertify through knowledge and rules testing, as well as hearing and vision exams. Railroads conduct operational tests by observing conductors performing tasks safely. Engineers undergo annual evaluations along with regular full-performance reviews. Railroads also monitor engineers to ensure they follow speed restrictions and stop signals.